Cheng Na, Lu Dudan, Xiang Tianxin, Tu Shangqing, Lai Lingling, Wu Xiaoping (Department of Infectious Diseases, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, Nanchang 330006)

Contemporary medical education in China emphasizes that talent cultivation should adapt to societal demands, aiming to produce medical students capable of analyzing, solving, and raising new problems—well-rounded individuals with strong professional skills and high comprehensive quality. Corresponding reforms in teaching methods have become a critical task for medical universities. Infectious diseases, a discipline requiring specialized knowledge, broad expertise, and diverse practical skills, faces rapid changes in disease spectra and emerging pathogens, placing higher demands on modern medical students. This study establishes a Problem-Based Learning (PBL) model tailored to the discipline’s characteristics, aiming to explore pathways for cultivating high-quality medical professionals.

A total of 108 undergraduate students majoring in clinical medicine (5-year program) at The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University were enrolled. Class 1 (n=54) received PBL-based instruction, while Class 2 (n=54) served as the control group with traditional lectures.

-

Intervention: The chapter "Dysentery" was taught using PBL for the experimental group, while traditional lectures were used for the control group. Other chapters followed traditional teaching for both groups.

-

PBL Structure:

-

Three 1-hour sessions (total 3 hours, equivalent to traditional teaching duration).

-

Pre-class: Case scenarios and guiding questions distributed for self-study via literature review (internet, library) and discussions.

-

In-class: Six student groups presented analyses and answers, with instructor guidance to correct errors and reinforce key points.

A questionnaire survey was administered post-instruction (100% response rate).

Data were analyzed using SPSS 19.0. Group comparisons were performed with p<0.05 indicating statistical significance.

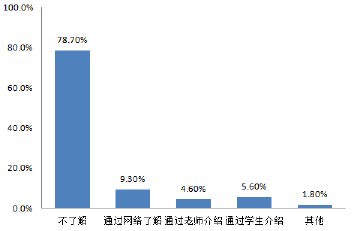

Prior to PBL implementation:

-

85/108 students were unfamiliar with PBL.

-

10 via online resources, 5 via instructors, 6 via peers, 2 via other channels.

Figure 1: Pre-teaching awareness of PBL.

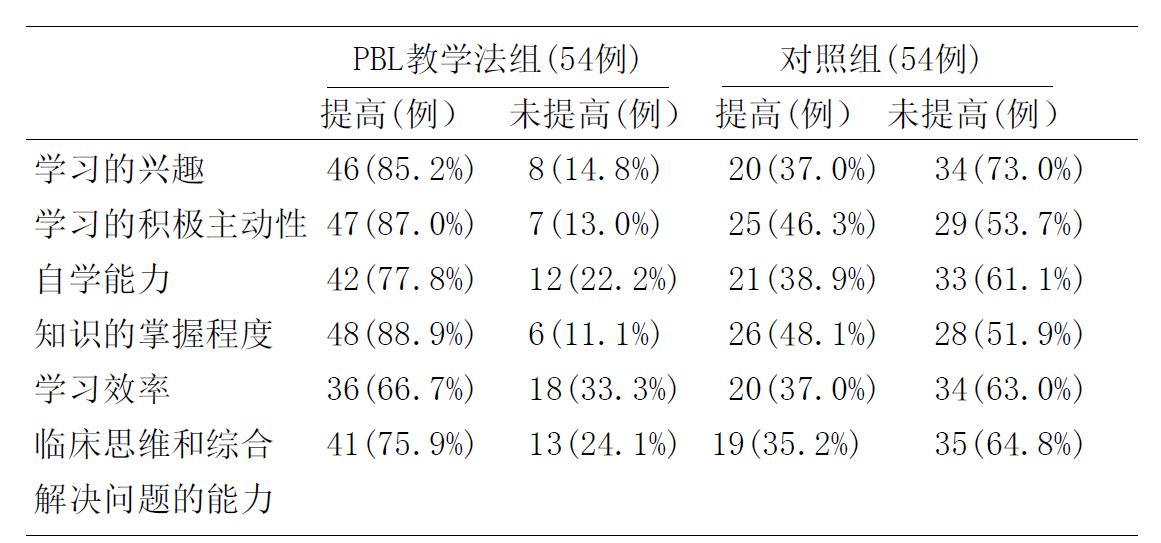

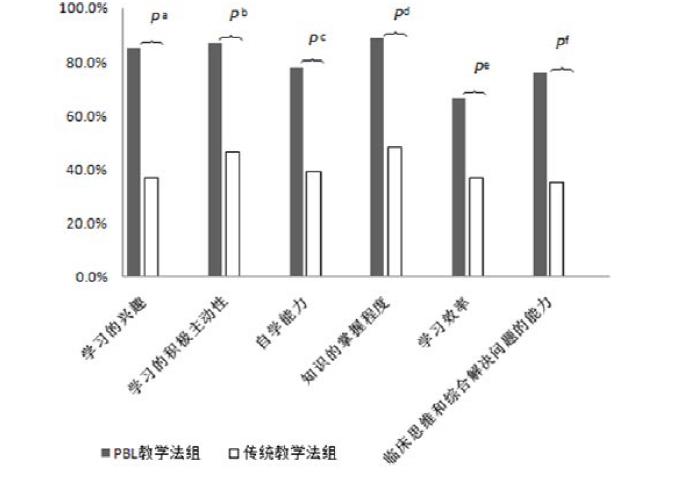

PBL group showed significant improvements compared to controls in:

-

Learning interest

-

Proactivity

-

Self-learning ability

-

Knowledge retention

-

Clinical reasoning

-

Problem-solving skills

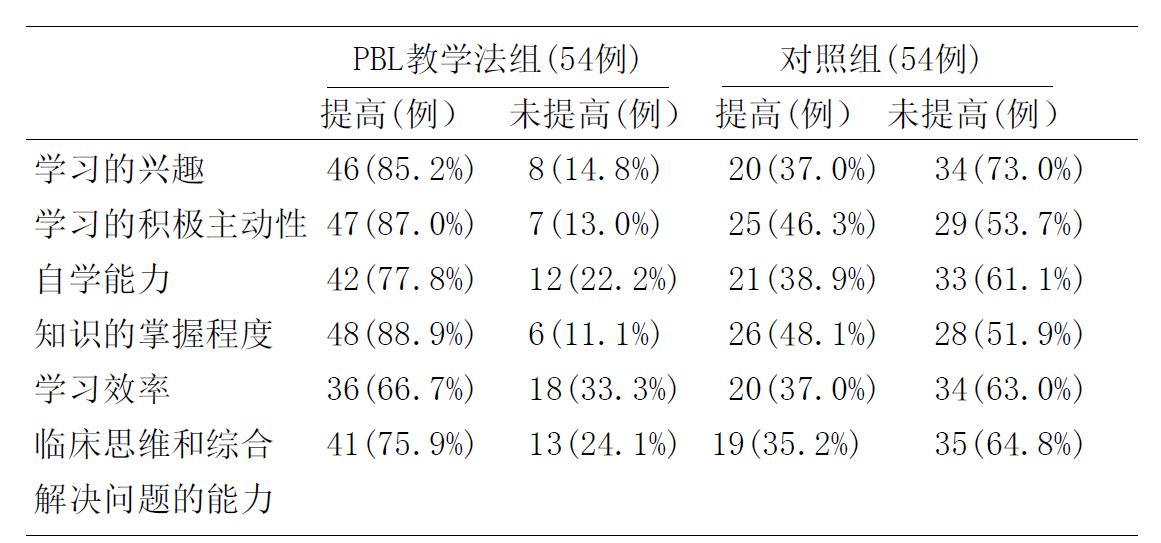

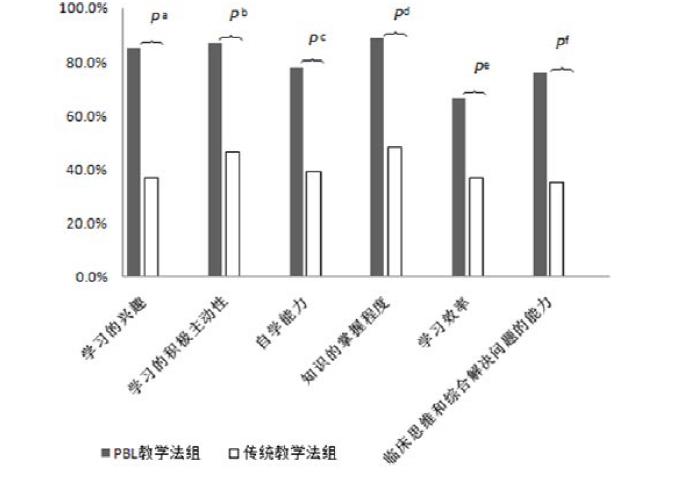

(p<0.05 for all, Table 1 and Figure 2).

Table 1: Comparison of self-assessed competencies between groups (n, %).

Figure 2: Self-learning ability improvement: PBL vs. traditional teaching.

-

Active Learning: Originated by Professor Barrows at McMaster University in 1969, PBL shifts passive knowledge absorption to problem-driven exploration, enhancing clinical reasoning and critical thinking.

-

Collaborative Skills: Group discussions foster teamwork—a cornerstone of medical practice—and improve communication and literature retrieval abilities.

-

Adaptability to Infectious Diseases: PBL aligns with the dynamic nature of infectious diseases, equipping students to handle evolving pathogens and disease patterns.

-

Case Design: Requires balancing curricular objectives with flexibility to guide student-led discussions.

-

Facilitation Skills: Instructors must synthesize divergent ideas, reinforce key concepts, and address knowledge gaps.

The proverb “Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day; teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime” underscores PBL’s value in cultivating independent learners. However, transitioning from traditional “cramming” education necessitates gradual implementation, with iterative improvements in PBL curriculum design and classroom delivery.

Given its demonstrated benefits, PBL should be expanded in infectious disease education to enhance teaching efficacy and student outcomes.